Alcohol is the most widely used drug in Australia and its misuse causes significant harm to individuals, families, and communities. In 2020, around 1 in 12 South Australians were daily drinkers and almost 1 in 6 drank at a level that put them at risk of alcohol-related harm.1

The national guidelines for alcohol consumption recommend no more than 10 standard drinks a week and no more than 4 standard drinks on any one day to reduce the risk of alcohol-related disease or injury.2 Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should not drink alcohol as it can harm the baby.

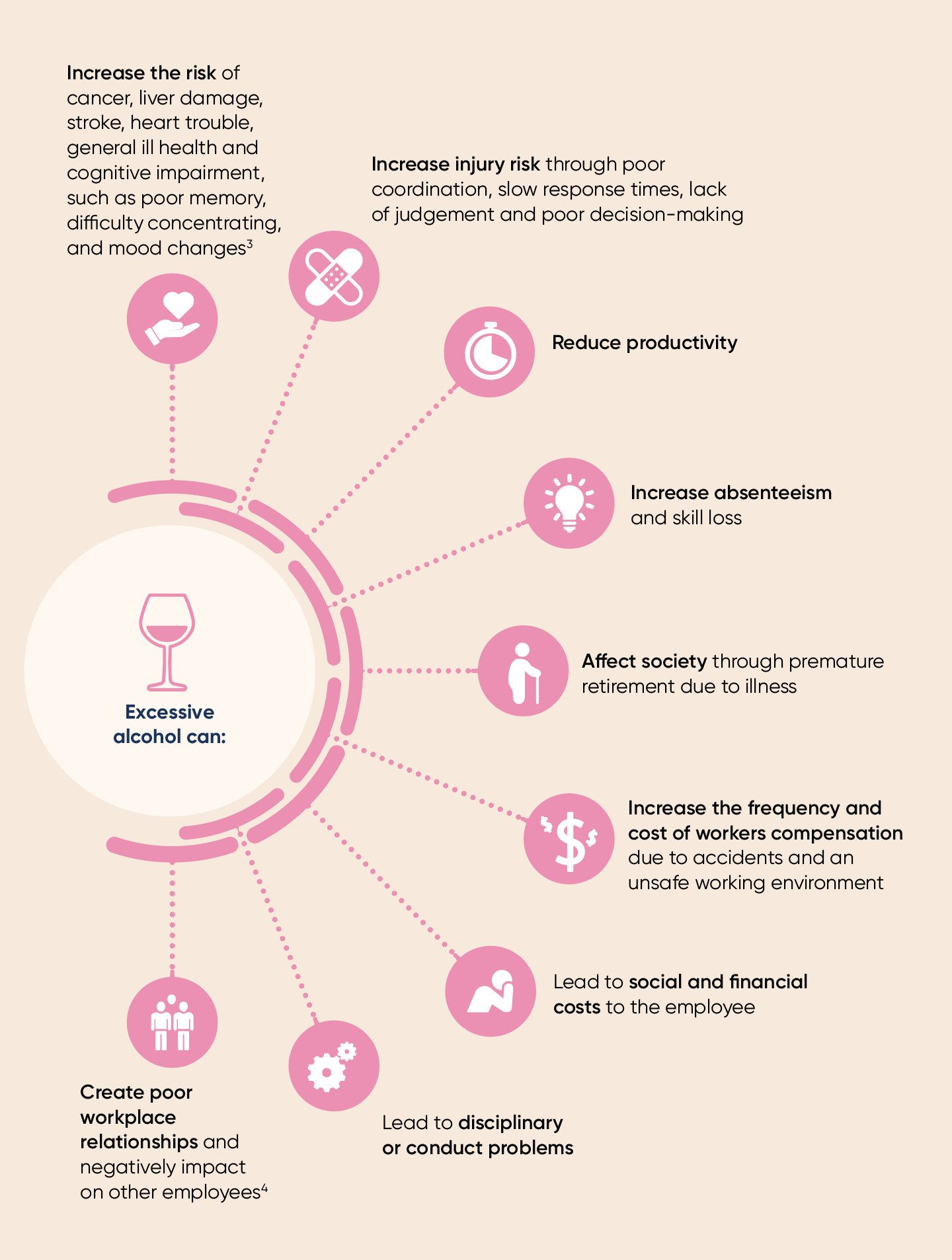

Drinking alcohol above these levels is known to be harmful to individuals, their families, and their colleagues, and it can be costly for employers.

Drinking is often involved in work social functions, meals and outings to celebrate team and individual successes, or informal after-work gatherings. Alcohol can also be used to relieve work-related stress and other issues.

Drinking alcohol at risky levels is more common among those who work than those who don’t.5 The culture and context of a workplace can shape people’s behaviour, including their patterns of alcohol consumption. Workplace factors that are known to increase risky alcohol consumption include:

- access to and availability of alcohol (such as at workplace functions)

- shift work

- working conditions (for example hazardous or dangerous work)

- interpersonal factors such as workplace bullying and conflict

- stressful workplace environment with unrealistic responsibilities, targets, and over or under work

- industry type

- workplace culture.6

Workplaces can promote healthy attitudes towards avoidance and responsible alcohol consumption through education and awareness. By supporting people to adopt healthy behaviours around alcohol consumption, you can benefit from a healthier and happier workforce and a safer workplace for everyone.

A formal alcohol policy is at the heart of preventing and managing alcohol-related behaviours in the workplace. The policy should be developed in consultation with employees, applied equally to all levels, and clearly state acceptable and unacceptable behaviours, including consequences. The policy and how it will be implemented should be clearly communicated to everyone in the organisation.

The following tables provide a combination of strategies to address alcohol consumption, ranging from changes in the physical environment and social culture to helping employees in their personal efforts to reduce their drinking.

Actions you can take to reduce alcohol consumption in the workplace

Healthy vision — create polices, practice and cultures to support responsible alcohol consumption

- In consultation with workers, develop and implement a formal workplace alcohol policy. This should include the responsible service of alcohol, how to respond to workers who are under the influence, any testing procedures, how your organisation provides support for individuals struggling with alcohol misuse, and provides education programs based on national guidelines (e.g. NHMRC).

- Include your alcohol policy and education information in induction materials.

- Lead by example and encourage management to be responsible drinkers.

- Consider your workplace’s customs, beliefs, attitudes, and traditions towards alcohol and facilitate or support practices where drinking isn’t expected or encouraged.

- Review employment practices and working conditions that might impact on employee stress (working hours, flexible working conditions, job design, workload, resources, bullying etc). This could be achieved using the ‘People at Work’ survey tool (peopleatwork.gov.au).

- Train managers or team leaders to recognise and respond appropriately to the negative impact of alcohol within the workplace.

- Use a risk management approach to prevent and manage alcohol-related harm and issues in the workplace.\

- Ensure alcohol is not used as prizes or gifts. Swap alcohol for gifts that promote wellbeing and health, such as vouchers for activities, plants, books, sports or baking equipment.

Healthy place — create a workplace environment that reduces alcohol consumption

- Display alcohol-related posters, including drink driving prevention posters and those showing the health and financial benefits of giving up alcohol.

- Don’t stock alcohol in the fridge or have it where employees can see it.

- Provide plenty of non-alcoholic drinks and food on occasions where alcohol is offered and ensure responsible service of alcohol.

- Provide alternative public transport options from workplace events where alcoholic beverages are served.

- Hold work functions around activities that don’t include drinking, such as movie nights, family days or sports activities, or have work social functions at times when alcohol isn’t expected, such as breakfast, morning tea, or lunch.

Healthy people — support workers to drink responsibly

- Educate workers on the safe consumption of alcohol, the harms of alcohol, the Australian drinking guidelines and on standard drink sizes.

- Highlight the positive aspects of reducing alcohol intake so workers clearly understand the benefits of cutting back or stopping altogether.

- Promote the use of support services such as the Alcohol and Drug Information Service (ADIS), employee assistance programs, and general practitioners and allow confidential access to these services during work hours.

- Help those who need help. Access to treatment is an important part of having a comprehensive approach to prevent and manage alcohol-related harm in the workplace. This should include support to find and get counselling and treatment, appropriate paid or unpaid leave to access treatment, and worker confidentiality.

More resources to help you take action

Alcohol resource referral guide (DOCX, 460.2 KB)

WorkLife has been designed to help workplaces respond to alcohol and drug issues and to develop alcohol and drug policies. worklife.finders.edu.au

The Alcohol and Drug Foundation has facts, information and resources on alcohol and other drugs.

SafeWork SA has dedicated information and advice related to alcohol and other drugs.

1 Wellbeing SA, South Australian population health survey 2020 annual report adults, Wellbeing SA, 2020; Australian Bureau of Statistics, Alcohol consumption 2017-18 state and territory findings, ABS, 2020, accessed August 2022.

2 National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol, NHMRC, 2020, accessed August 2022.

3 World Cancer Research Fund, Continuous update project (CUP) matrix London, UK, World Cancer Research Fund, 2018.

4 WHO, Global status report on alcohol and health 2018, WHO, 2018; R Cercarelli, S Allsop, M Evans and F Velander, Reducing alcohol-related harm in the workplace: an evidence review, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2012; T Sullivan, F Edgar and I McAndrew, ‘The hidden costs of employee drinking: A quantitative analysis’, Drug Alcohol Rev., 2019, 38: 543-553; K Buvik, I Synnøve Moan and T Halkjelsvik, ‘Alcohol-related absence and presenteeism: Beyond productivity loss’, International Journal of Drug Policy, 2018, 58:71-77; CE Dale and MJ Livingston, ‘The burden of alcohol drinking on co-workers in the Australian workplace’, The Medical Journal of Australia, 2010, 193(3):138-140; T Chikritzhs and M Livingston, ‘Alcohol and the risk of injury’, Nutrients, 2021, 13(8):2777; T Korhonen, E Smeds, K Silventoinen, K Heikkila and J Kapiro, ‘Cigarette smoking and alcohol use as predictors of disability retirement: A population-based cohort study’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2015, 155:260-266; S Whetton, RJ Tait, W Gilmore, T Dey, S Agramunt, S Abdul Halim, A McEntee, A Mukhtar, A Roche, S Allsop, and T Chikritzhs, Examining the social and economic costs of alcohol use in Australia: 2017/18, National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University, 2021.

5 AIHW, National Drug Strategy Household Survey Canberra, AIHW, 2020.

6 MR Frone and AL Brown, ‘Workplace substance-use norms as predictors of employee substance use and impairment: A survey of U.S. workers’, Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 2010, 71(4):526-34; AM Roche, NK Lee, S Battams, JA Fischer, J Cameron J and A McEntee, ‘Alcohol use among workers in male-dominated industries: A systematic review of risk factors’, Safety Science, 2015, 78:124-41; MR Frone, ‘Work stress and alcohol use: developing and testing a biphasic self-medication model’, Work & Stress, 2016, 30(4):374-94; PJ Schluter, C Turner and C Benefer, ‘Long working hours and alcohol risk among Australian and New Zealand nurses and midwives: A cross-sectional study’, International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2012, 49(6):701-9; MR Frone and JR Trinidad, Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 2014, 28(4):1271-1277, doi: 10.1037/a0037785; K Richter K, A Rodenbeck, HG Weess, SG Riedel-Heller and T Hillemacher, ‘Shiftwork and alcohol consumption: A systematic review of the literature’, European Addiction Research, 2021, 27(1), 9-15; G Marins, L Cunha and M Lacomblez, ‘Dangerous and precarious work and the high cost of emotional demands controlled by alcohol: A systematic review’. In: Arezes P. et al. (eds) Occupational and environmental safety and health. studies in systems, decision and control, Springer, 2019 (202); M Birkeland Nielsen, J Gjerstad and MR Frone, ‘Alcohol use and psychosocial stressors in the Norwegian workforce’, Substance Use & Misuse, 2018, 53 (4) 574-584; MR Frone, ‘Workplace substance use climate: prevalence and distribution in the U.S. workforce’, Journal of Substance Use, 2012, 17(1):72-83.